EPISODE 1: Poulenc's Calligrammes

Jeremy Boulton (operatic baritone) and Su Hee Cho (piano) perform Poulenc's 'Calligrammes' cycle as Jeremy dissects the work's finer details. Original music by John Spence. johnspence.net.au/

In 1952, four years after commencing work on his Calligrammes, the most avant-garde of today’s composers, Francis Poulenc, reflected on his setting of Guilliame Apollinaire’s poetry. He noted ‘The more I turn the pages of this volume, the more I feel that I shall no longer find what I need. Not that I like the poetry of Apollinaire any less (I have never liked it so much), but I feel I have exhausted all that is suitable for me.’

The texts of Calligrammes originate from a 1918 volume of Apollinaire’s poetry Calligrammes, Poems of Peace and War (1913-1916). Several poems in this volume are published as ideograms, including three which Poulenc set in this cycle. Of the poems selected by Poulenc, two set (‘Voyage’ and ‘Il pleut’) are of peace whilst the others are of war. Although Apollinaire was a foreigner, he enlisted in the French army in 1914 and the poetry reflects his life as a solider and his peculiar, yet distinctive voice in depicting his experience of war.

Apollinaire was also the individual that coined the term ‘Orphism’ in 1912, an offshoot of the Cubism movement. It referred to the use of pure abstraction and bright colours. Artists included František Kupka, Robert Delaunay and his wife Sonia Delaunay.

‘L’Espionne’ (The Spy) is considered by Pierre Bernarc (Poulenc’s collaborator and the artist for which this work was originally composed) to be a moment of ‘refuge’ for Apollinaire during his time at the front. In the poem he is likely referring to his fiancée at the time, Madeleine Pagés as a ‘lovely fortress’ that he was only able to hold in his arms for one hour of a single day. The most lyrical of Poulenc’s settings in this cycle, it is littered with specific dynamics prompting a generous palate of colours from the performer.

‘Mutation’ marks a seismic shift in mood from its predecessor. The poetry of Apollinaire conjures a patchwork of seemingly disconnected images from weeping women, marching soldiers, a lock gate keeper fishing, shells exploding to the white chalk of the trenches of Champagne. Each image establishes a contrasting mood and dynamic, often suddenly and without preparation. The repeated ‘Eh! Oh! Ah!’ motif suggests the various reactions to these images as they are considered. The poet is (somewhat) resolved at maintaining his love for his sweetheart, despite the chaos immediately surrounding him.

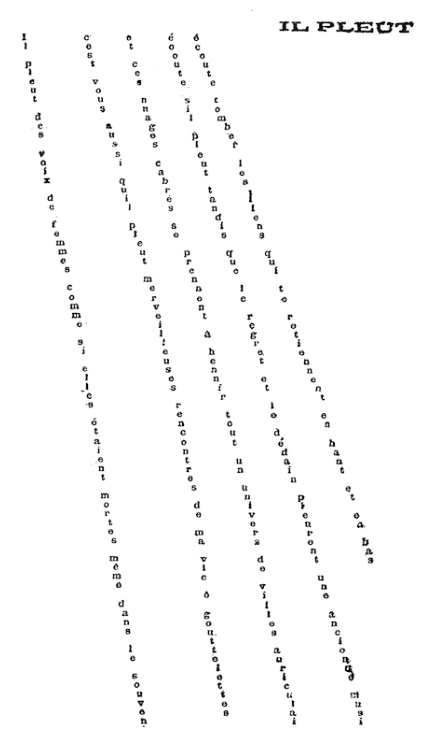

‘Vers le sud’ (Towards the South) is a ‘poem of regret’ for happier days based around his time in the south of France with his mistress Louise de Coligny Chatillon. The repeated references to the pomegranate tree, its flowers, and the text ‘our hearts hang together on the same pomegranate tree’ is littered with the symbolism of Greek mythology where the pomegranate is often considered a symbol of sexual awakening. A [perhaps] cruel irony is achieved with the tonal mixture of minor to major chords that bookend the piece. ‘Il pleut’ (It Rains) is printed in five almost vertical and parallel lines suggesting rain (pictured). Poulenc states ‘From the technical point of view, it is in the field of subtlety of pianistic writing that I was experimenting here, attempting in ‘Il pleut’ to achieve a kind of musical calligram.’ The piano part is incomparably more complex than the one for the voice and right at the mid-point of the cycle, it is clear Poulenc attempts to reverse the roles of pianist and vocalist. ‘La grâce exilée’ (Exiled Grace) is poignant in its central metaphor – the colours of nation’s flags taking the place of the exiled love and beauty of Apollinaire’s lover, Marie Laurencin who left France for Spain at this time. Affectionately, Apollinaire likens Laurencin to an Infanta – a young Spanish princess. A charming and affectionate, yet melancholic atmosphere is created in this most brief song.

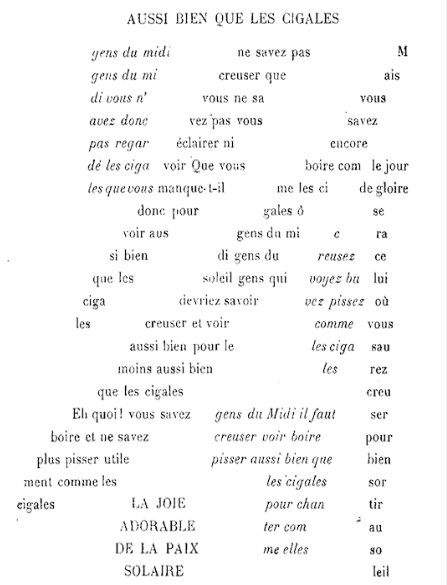

‘Aussi bien que les cigales’ (As well as the cicadas) is described by Poulenc as ‘half-way between a chanson (ribald or folk) and a true mélodie.’ He is addressing his comrades in this poem (perhaps those of an artillery regiment at Montpellier) in a somewhat drunken, outrageous manner. He compares the men in the regiment to cicadas whose existence is to dig, ‘piss’ [sic] and drink. He jokes that the only task his comrades are capable of is the latter. A line that reads bizarrely ‘pissez utilement’ (to-piss usefully) refers to how cicadas ‘use excess fluid to help moisten and remould their tunnels & cells’ and ‘they might, in some cases, even use it to keep ants from attacking’, likening the men in the trenches to mere insects in the mud. The final climax featuring a typical coda in Poulenc’s style sees a dramatic change to a slow tempo to convey the shining of the sun into the dark and damp trenches as the men (or cicadas) emerge into the light, heralding in a new day.

‘Voyage’, (Journey) the final piece in the cycle is referred to by Bernarc as one of the two poems of peace along with ‘Il pleut’. Poulenc writes fondly and extensively of this closing piece: ‘By the interjection of unexpected and sensitive modulations, ‘Voyage’ goes from emotion to silence, passing through melancholy and love.’ ‘The end is, for me, the silence of a night in July when, on the terrace of my childhood home at Nogent, I heard in the distance the trains ‘that were leaving on holiday’ (as I used to think then).’

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorJeremy Boulton |